August 2024 / STRATEGY SPOTLIGHT

Growing government debt has raised concerns. Should it?

We believe governments have time and options to address historically high debt-to-gross domestic product levels

Key Insights

- Rising sovereign debt levels in developed markets have increased concerns about when and how much debt is too much. In our view, it’s not time to worry yet.

- Attention to debt sustainability in G10 nations has been piqued as higher interest costs and large deficits weigh on debt metrics.

- We view the U.S., UK, France, Italy, and Japan as the most vulnerable economies and discuss investment implications for their options to address their debt.

Debts incurred to support economies during the global financial crisis and the pandemic have pushed developed market countries’ debt‑to‑gross‑domestic‑product (GDP) ratios to historical peace‑time highs. Currently, public debt‑to‑GDP ratios for developed market countries are just over 100% on average, which is raising concerns about whether current levels of debt are too high for the debt ratios to stabilize. Issues such as some weaker U.S. Treasury auctions and significant elections in France, the UK, and the U.S. have heightened attention to the subject of debt sustainability.

But how much debt can a nation carry sustainably? Researchers have attempted to pinpoint a threshold public debt‑to‑GDP ratio that would lead to fiscal dominance, which is when a nation’s debt and deficit become so large that they blunt monetary policy’s ability to effectively control inflation. The answer is not clear, forcing policymakers to select what they deem appropriate for their respective countries. The European Union (EU) has instituted fiscal rules for member states that require a less than 60% public debt‑to‑GDP ratio. In contrast, the Penn Wharton Budget group estimated that 200% is the likely threshold for the U.S.

Why does it matter?

Generally, as debt‑to‑GDP ratios rise, so do the economic costs (crowding out investments) as governments have to spend more on interest expenses, leaving fewer resources to allocate to other uses. This blunts growth potential, which would further pressure debt‑to‑GDP metrics by lowering GDP growth.

In general, debt sustainability is a function of a country’s primary fiscal balance—the government’s revenues minus expenses excluding interest payments, its real growth rate (g), and its real interest rates (r), i.e., average interest rate of government debt less inflation rate. If real rates are higher than real growth, debt ratios will rise without a primary surplus. However, if real growth is higher than real rates, debt ratios can fall—or the economy could support a small primary fiscal deficit. In other words, to keep public debt‑to‑GDP ratios from growing, a country’s fiscal balance must be in line with the difference between real interest rates and real growth rates.

Four key debt dynamics and the countries most at risk

(Fig. 1) Each country’s debt dynamics present unique issues.

As of July 2024.

Source: T. Rowe Price.

Which nations are most vulnerable?

We analyzed developed nations’ debt dynamics in several ways to determine which countries seem most at risk:

Large gross debt to GDP. Public debt‑to‑GDP figures provide an overview of which economies could be carrying too much debt. Several developed market countries have debt‑to‑GDP ratios over 100%, most notably Japan at over 250%, the highest level in the world. Italy, the U.S., and France each carry ratios over 110%.

Interest rate and growth dynamics. The relationship between real interest rates and real growth rates influences an economy’s ability to contain debt depending on the country’s primary balance. Italy appears to be under the most pressure to constrain its fiscal balance due to its structurally low growth rate and higher market interest rates. The UK and France similarly have higher real interest rates than real growth rates, highlighting one of the risks of increasing debt.

Fiscal deficits. Without supportive growth and interest rate dynamics, fiscal deficits will add to debt levels. The U.S., Japan, Italy, France, and the UK all run significant fiscal deficits, with the U.S.’s yawning 8.8% of GDP deficit1 leading the group.

Future interest expenses. We multiplied each country’s debt‑to‑GDP ratio by the prevailing 10‑year government bond yield as a proxy for the effects of future interest expense on the country’s debt burden—this assumes all outstanding debt would be renewed at the prevailing market rate and no change to the level of debt. By this metric, the U.S., the UK, and Italy will face a notable drag due to interest expenses.

Time provides a buffer. The low interest environment that prevailed over the last decade paired with the long maturity of debt issued have provided governments time to address their very high public debt ratios. Debt sustainability is not a pressing issue at this moment despite our outlook for debt to continue rising.

As governments refinance maturing debt at higher rates, interest expenses will rise. This will not have an immediate impact, but if nothing changes, higher interest and significant deficits will snowball. This impact would be even more significant if real interest rates increased. In our view, uncertainty regarding future interest rates could contribute to the lack of fiscal prudence as countries do not appear to be in a particular rush to address high fiscal deficits.

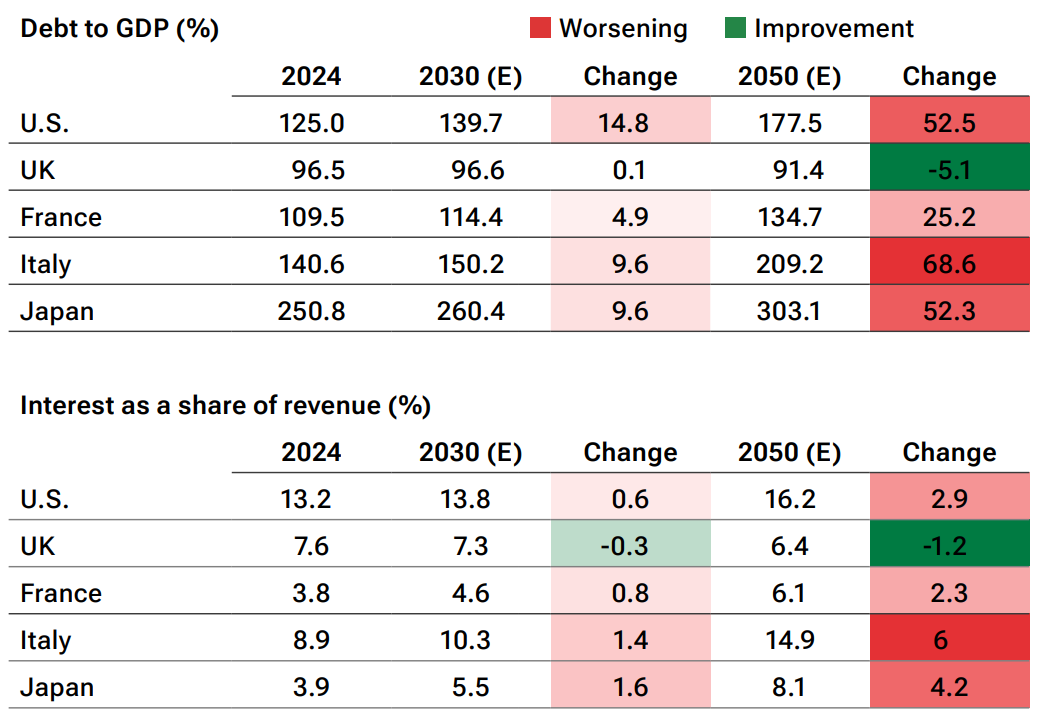

Debt and interest expense largely worsen

(Fig. 2) Debt‑to‑GDP and interest expense ratios increase

As of March 2024.

Shading represents intensity.

Source: European Commission AMECO database.

Projected estimates (E) are based on T. Rowe Price assumptions regarding future economic growth, inflation, and interest rates. T. Rowe Price cautions that economic estimates and forward‑looking statements are subject to numerous assumptions, risks, and uncertainties, which change over time. Actual outcomes could differ materially from those anticipated in estimates and forward‑looking statements, and future results could differ materially from historical performance. The information presented herein is shown for illustrative, informational purposes only. Any historical data used as a basis for analysis are based on information gathered by T. Rowe Price and from third‑party sources and have not been verified. Forecasts are based on subjective estimates about market environments that may never occur. Any forward‑looking statements speak only as of the date they are made. T. Rowe Price assumes no duty to, and does not undertake to, update forward‑looking statements.

Methods to stabilize debt‑to‑GDP ratios

The two most likely scenarios that governments in developed countries would pursue to address rising public sector debt are fiscal consolidation and a combination of inflation and financial repression.

Fiscal consolidation. Fiscal consolidation, through lower government spending, higher taxes, or both, could be an option for these vulnerable countries as required adjustments remain modest, but fiscal consolidation is difficult.

What does it take to successfully implement a fiscal adjustment?

- Voters have a clear understanding of why prudent fiscal policies are important.

- A medium‑term plan with binding limits and other fiscal rules.

- Specific plans for upside and downside growth surprises.

Inflation and financial repression. When fiscal consolidation efforts are unsuccessful or unfeasible, governments can also address their domestic debt (debt denominated in local currency) via inflation and financial repression.

How can countries use inflation and repression to address existing debt?

- Elevated inflation levels reduce the future value of current debt, making debt more manageable by allowing inflation to run at higher levels.

- Policies, such as quantitative easing, yield controls, or bank reserves or liquidity requirements that indirectly channel funds to government use, typically at below‑market rates, can help governments stabilize debt levels.

Motivation to act

What would spur governments into action? If market pressures were to translate into failed government debt auctions, or if there was an evaporation of liquidity from the secondary markets or if there were rising sovereign credit spreads, then the likelihood that a nation would take steps to stabilize its debts would increase.

In our view, the U.S., the UK, and Japan are likely to continue loose fiscal policies for now, as their debt sustainability risks are not immediate. France and Italy are the most likely to engage in gradual deficit reductions, influenced by eurozone fiscal rules and monetary policy implemented on a pan‑European scale. However, France’s newly elected “hung parliament” could make budget decisions more contentious, putting prudent fiscal policy in jeopardy.

Over the medium term, we see a higher probability for inflation spikes and financial repression in the U.S., the UK, and Japan if debt sustainability risks increase.

Investment implications

The sizable debt‑to‑GDP levels of select developed market countries is a growing concern, but the issue does not need to be addressed immediately. There are also different methods that governments can use to tackle debt sustainability issues.

The method a country employs to address its debt sustainability leads to some likely outcomes and can create unique investment opportunities. Should governments choose fiscal consolidation, a clear implication would be for a fiscal drag on growth for the next several years, creating disinflationary pressure. This would allow for lower rates, which we believe would create opportunities in a country’s domestic debt, as these positions could be attractive amid falling yields. Conversely, the country’s currency could become less valuable.

If governments choose financial repression and inflation, elevated and volatile inflation would be a likely reaction. In our view, this process for addressing debt stability would evolve in two stages: In the first stage, elevated inflation would cause longer‑term rates to increase. In this case, we would look for opportunities to take advantage of a steepening yield curve. Inflation‑linked bonds could also be attractive. In the second stage of this strategy to improve debt sustainability, higher market rates could encourage officials to implement financial repression measures to bring rates down.

IMPORTANT INFORMATION

This material is being furnished for general informational and/or marketing purposes only. The material does not constitute or undertake to give advice of any nature, including fiduciary investment advice, nor is it intended to serve as the primary basis for an investment decision. Prospective investors are recommended to seek independent legal, financial and tax advice before making any investment decision. T. Rowe Price group of companies including T. Rowe Price Associates, Inc. and/or its affiliates receive revenue from T. Rowe Price investment products and services. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. The value of an investment and any income from it can go down as well as up. Investors may get back less than the amount invested.

The material does not constitute a distribution, an offer, an invitation, a personal or general recommendation or solicitation to sell or buy any securities in any jurisdiction or to conduct any particular investment activity. The material has not been reviewed by any regulatory authority in any jurisdiction.

Information and opinions presented have been obtained or derived from sources believed to be reliable and current; however, we cannot guarantee the sources' accuracy or completeness. There is no guarantee that any forecasts made will come to pass. The views contained herein are as of the date noted on the material and are subject to change without notice; these views may differ from those of other T. Rowe Price group companies and/or associates. Under no circumstances should the material, in whole or in part, be copied or redistributed without consent from T. Rowe Price.

The material is not intended for use by persons in jurisdictions which prohibit or restrict the distribution of the material and in certain countries the material is provided upon specific request.

It is not intended for distribution to retail investors in any jurisdiction.