personal finance | january 27, 2025

How spenders can save more: Key insights from our latest study

Our latest study revealed behaviors that might help spenders save.

Key Insights

Understanding your spending personality type can help you plan and save for your goals more successfully.

Spenders and savers both place a high personal value on providing security and support for their families, but spenders tend to carry a higher degree of financial stress.

For spenders who aspire to become savers, techniques such as building a budget and automating their savings plan can move them in the right direction.

Lindsay Theodore, CFP®

Thought Leadership Senior Manager

Our 2023 Retirement Savings and Spending Study uncovered several connections between savings motivations, money behaviors, and financial stress levels according to an individual’s financial personality type (saver, spender, or somewhere in the middle). Understanding which of these personalities you connect with more closely can help you lay out a retirement savings plan that addresses your inclinations and biases. If you’re unsure of where you fall on the spectrum, take the short quiz “What’s your spending personality?” to better understand your spending/saving persona.

Saver vs. spender similarities and differences

In our 2023 study, we asked workers under age 50 to subjectively identify the money personality that best describes them and then answer a series of questions regarding their finances. Thirty percent (30%) identified as savers, 20% as spenders, and 50% as a saver/spender combination. Generally, median income was higher for savers, but not all savers reported above-average income. Twenty‑nine percent (29%) reported incomes under $75,000 (2022 median household income according to the Census Bureau)—meaning that one doesn’t necessarily need to earn a high income to be a saver. Here are some of the trends we observed regarding saver versus spender attitudes and behaviors, followed by some actions that could help spenders save more.

What’s your spending personality?

Which best describes your spending/saving behavior?

1. I spend most of my paycheck (and sometimes more).

2. I spend whatever I need to maintain my lifestyle.

3. I spend a set amount each month and sometimes save what’s left over.

4. I save a set amount each month and spend only what’s left over.

5. I save as much as I can and have difficulty spending money.

Which best describes your credit card usage?

1. I always carry a balance from month to month.

2. I sometimes carry a balance.

3. I rarely carry a balance.

4. I pay off my balance every month.

5. I don’t use credit cards.

What are you most likely to do with a cash windfall such as a bonus or tax refund?

1. Spend most or all of it.

2. Pay down credit card balances, and spend the rest.

3. Spend some, and save some.

4. Save most, and spend some.

5. Save or invest it all.

What is your reaction to the statement “My current savings balances give me a sense of security and peace of mind”?

1. I value my lifestyle more than my savings account balances.

2. It would, but I don’t have enough saved to feel secure currently.

3. I think I maintain a proper balance between supporting my lifestyle and saving.

4. Yes, but I think I could save more.

5. Yes, my current savings give me a sense of security and peace of mind.

How often do you make impulsive purchases?

1. Very often

2. Often

3. Occasionally

4. Rarely

5. Never

Add up your responses and divide by five.

Resulting score classifications

Savers—score of 4–5

Middle of the road—score of 3

Spenders—score of 1–2

Saving motivations and limitations. Both spenders and savers reported providing for their families and funding large purchases as key motivations to save (Fig. 1). For savers, the most common saving motivation is achieving a sense of safety and security. For spenders, a major limitation is the feeling that they don’t have the means to save. However, 52% of spenders earn more than median U.S. household income (with 27% earning over $125,000 per year), and 43% of spenders reported either supporting their families or achieving a sense of safety as an important driver for saving when they do. This indicates that the desire to save is often present, even if the perceived or actual means to save is not.

Thoughts on saving—saver vs. spender

(Fig. 1) Spenders are more likely to cite limited means as a roadblock for saving

Source: T. Rowe Price Retirement Savings and Spending Study (2023). Respondents under age 50 were asked to select the statement that most closely resembles their thoughts on saving.

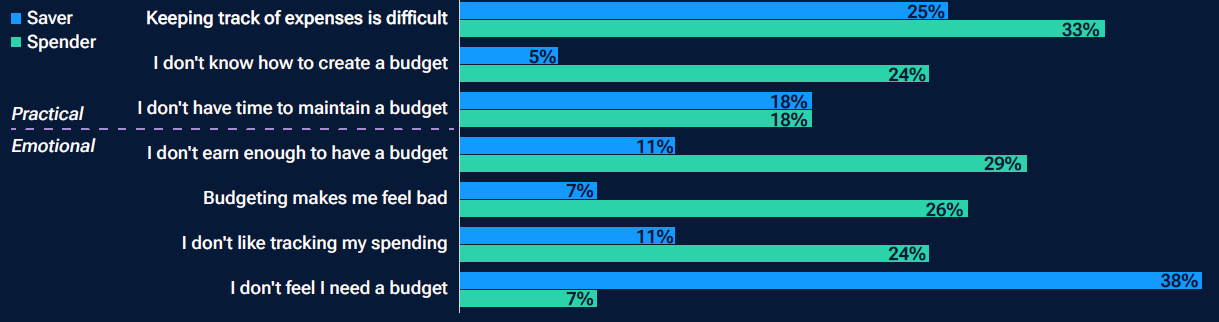

Budgeting behaviors. Generally, savers are better about having and sticking to a budget. Sixty-four percent (64%) of savers and 37% of spenders reported maintaining a budget, and 45% of savers and 8% of spenders reported both having and adhering to a budget every month. When asked why they don’t budget, spenders provided multiple practical and emotional reasons (such as finding it difficult, time‑consuming, or unpleasant). However, only 7% reported not needing to maintain a budget. Therefore, spenders could probably benefit from having one (Fig. 2).

Budgeting views—saver vs. spender

(Fig. 2) Spenders are reluctant to budget for both practical and emotional reasons

Source: T. Rowe Price Retirement Savings and Spending Study (2023). Respondents under age 50 were asked: Which of the following are reasons why you do not maintain a monthly budget? Respondents could select multiple reasons for not maintaining a budget.

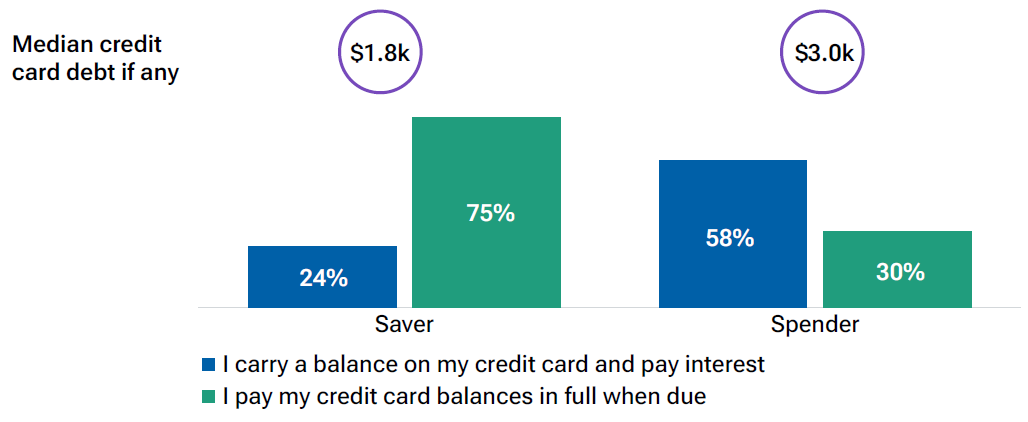

Credit card usage and views on debt. Credit card balance carryover is more common among spenders. Fifty-eight percent (58%) of spenders regularly carry a balance on credit cards, versus 24% of savers (Fig. 3). Compared with savers, spenders tend to carry higher non-mortgage debt balances (credit card, personal and student loan, etc.), which might explain why they have a less favorable view of debt overall.

Credit card habits—saver vs. spender

(Fig. 3) Spenders tend to carry more credit card debt

Source: T. Rowe Price Retirement Savings and Spending Study (2023). Respondents under age 50 were asked to indicate the current outstanding amount of each type of debt held by their household and how often they carry or pay off their credit card balance each month (always or often).

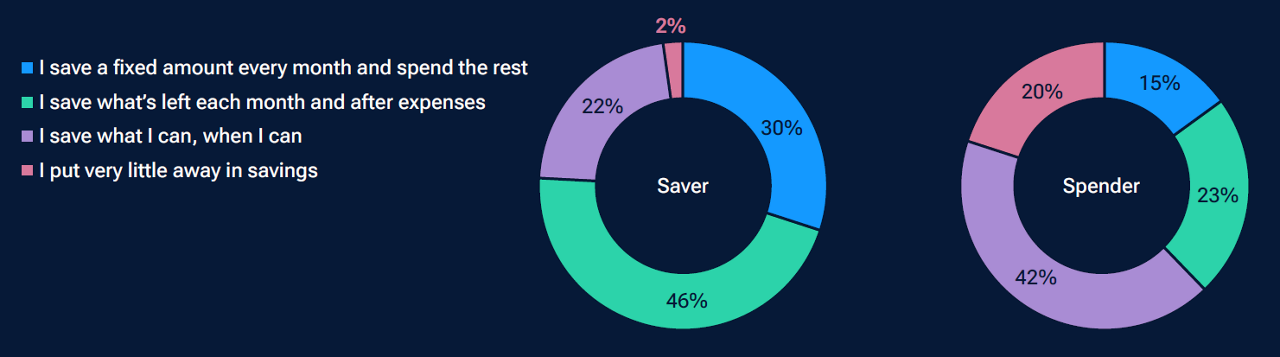

Savings habits. We observed that 30% of savers set aside a fixed amount every month, compared with only 15% of spenders. So, while savers tend to adjust their fixed and discretionary expenses around a set periodic savings amount, spenders take a more passive savings approach and are more likely to base their savings on what’s left over after spending—if they manage to save at all (Fig. 4).

How spenders and savers go about saving

(Fig. 4) Spenders take a more passive approach to saving

Source: T. Rowe Price Retirement Savings and Spending Study (2023). Respondents under age 50 were asked to cite the statement that best describes how they go about saving.

Levels of financial stress. Savers and spenders experience significantly different levels of financial stress. Where 34% of savers reported a high or extremely high level of financial stress, twice as many spenders (68%) reported the same degree of financial unease (Fig. 5).

Overall level of financial stress—saver vs. spender

(Fig. 5) Spenders reported higher levels of financial stress

Source: T. Rowe Price Retirement Savings and Spending Study (2023). Respondents under age 50 were asked to rate their overall level of financial stress on a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 is not stressed at all and 10 is extremely stressed.

Ways to think and act more like a saver

Ultimately, we found that savers seek to provide for their families and achieve a sense of safety through an active savings approach and consistent budgeting. Similarly, when spenders manage to save, providing security and support for their families is a powerful motivator.

Perhaps spenders experience greater financial stress because they value financial security and realize they should probably be sticking to a budget and saving more. If you can identify with the latter situation, and would like to transition from spender or middle of the road to more of a saver, here are a few actions that could help nudge you in that direction:

1. Don’t shy away from budgeting.

A household budget is a spending plan that helps you set priorities, targets, and limits on where your money is being directed each month. Keep it simple and start with the basics.

Start by adding up your ongoing, somewhat fixed monthly expenses (housing, utilities, internet/cable, cellphone, loan payments, subscriptions, etc.).

Then, spend one hour per week totaling up your variable expenses for the previous week (groceries, gas, household goods, dinners out, clothing purchases, travel, entertainment, etc.).

Once you’ve done this for several months, you should have a better understanding of how you’re spending your money. From there, you can find opportunities to set limits, reduce expenses, and increase your savings rate. The attached worksheet (PDF) can help you get started. For practical ideas on how to cut spending to increase savings, see our recent article on ways you can spend less to save more.

Subscribe to T. Rowe Price Insights

Receive monthly retirement guidance, financial planning tips, and market updates straight to your inbox.

2. Rethink your relationship with credit cards.

While credit cards can be crucial tools for bridging occasional cash flow gaps and are utilized by both savers and spenders, regularly carrying balances can lead to additional interest charges and increased stress.

Halt use of credit cards if you carry balances. Over time, instead of using future income to pay down balances for past expenses, you’ll have the freedom to direct cash flows to savings and current expenses. This may mean dialing back on spending, but reducing your dependence on credit cards could lead to major mental and financial benefits.

Beware of using credit cards to amass credit card points, especially if you regularly carry over a balance. Credit card points can be attractive, but points often have restrictions or time limits, and the allure of the program may prompt you to spend more than you should. For instance, to earn enough airline mile points for a free flight, you may need to spend several thousands of dollars on your credit card for a trip that might cost under $500 outright. In most cases, saving the dollars you would have spent to earn points is a better decision.

3. Get your savings plan on autopilot.

To move from a passive to proactive savings approach, set up an automatic investment plan where a fixed dollar amount is taken directly from your paycheck and/or checking account and invested in a savings vehicle each month.

If your employer offers a 401(k), ensure that you’re contributing at least what’s needed to receive your company match. Typically, 401(k) contributions are automatically deducted from your paycheck.

If you don’t have a workplace plan, or you want to invest beyond it, you can set up an automatic investment plan with an individual retirement account (IRA) or taxable investment account.

Automating your investment plan can save you time, help you avoid emotional investing, and ensure that you’re paying yourself first. The key is to automate the plan so the money is set aside before you can be tempted to spend it.

Start with an amount you’re confident that you can stick to, then increase it. That way, you won’t have the deflating experience of needing to dip into savings soon after you start.

4. Enroll in an automatic contribution increase plan within your 401(k) or other employer-sponsored plan.

With an auto-increase plan, you can direct your employer to automatically increase the percentage of your income you contribute to your retirement plan each year. Every 1% to 2% annual increase can help you gradually progress toward the 15% annual savings rate T. Rowe Price recommends. Many workplace plans offer this service, and you can typically turn off or adjust your auto-increases at any time.

Like savers, spenders place a high value on supporting and achieving financial security for their families. But reluctance or lack of knowledge about money management fundamentals can cause anyone to fall short of feeling financial peace of mind. If you’re inclined to spend over saving and carry a higher degree of financial unease as a result, incorporating actions such as budgeting and automating your savings plan can help you better balance lifestyle enjoyment today with financial security tomorrow.

Retirement Savings and Spending Study

The Retirement Savings and Spending Study is a nationally representative online survey of 401(k) plan participants and retirees. The survey has been fielded annually since 2014. The 2023 survey was conducted between July 24, 2023, and August 13, 2023. It included 3,041 401(k) participants, full-time or part-time workers who never retired, currently age 18 or older, and either contributing to a 401(k) plan or eligible to contribute with a balance of $1,000 or more. The survey also included 1,176 retirees who have retired with a Rollover IRA or left-in-plan 401(k) balance.

Important Information

The views contained herein are those of the authors as of February 2024 and are subject to change without notice; these views may differ from those of other T. Rowe Price associates.

This material is provided for general and educational purposes only and is not intended to provide legal, tax, or investment advice. This material does not provide recommendations concerning investments, investment strategies, or account types; it is not individualized to the needs of any specific investor and is not intended to suggest that any particular investment action is appropriate for you, nor is it intended to serve as a primary basis for investment decision-making.

All charts and tables are shown for illustrative purposes only.

View investment professional background on FINRA's BrokerCheck.

202403-3462184

Next Steps

Learn how you can get on track to retire.

Contact a Financial Consultant at 1-800-401-1819.