asset allocation | May 3, 2024

Momentum: Don’t fear the reapers (of high profits)

History shows that momentum-driven markets don’t necessarily lead to market downturns.

Key Insights

History suggests that momentum-driven markets, if they are accompanied by strong fundamentals, need not result in market tumbles.

A fully invested and balanced approach, with disciplined rebalancing from growth toward value, leading to a tilt toward value, seems warranted.

Unlike the “junk rally” in the dot-com era, today’s top-performing tech stocks have strong fundamentals.

Sébastien Page

Head of Global Multi-Asset and CIO

Are YOLO and FOMO driving MOMO?

I don’t like acronyms, but I can’t help it in this case. The momentum factor (MOMO) has been performing better than during any rolling 12-month period since at least the early 1990s. Over the last several months, you would have done very well if you had picked the top-performing stocks based on past performance. What goes up keeps going up, it seems.

It’s not supposed to work that way. Finance theory—and every money manager pitch book—says that past returns aren’t indicative of future returns. Besides, trees don’t grow to the sky.

Or do they? What if they bear fruit in the form of high-performing computer chips for artificial intelligence? Will you risk missing out on what may be a once-in‑a‑lifetime opportunity in a new technology?

Therefore, the question at hand (IMHO):

Is this momentum-oriented market being driven by “you only live once” and “fear of missing out?”

Subscribe to T. Rowe Price Insights

Receive monthly retirement guidance, financial planning tips, and market updates straight to your inbox.

Our analysis

Over the last two weeks, my colleagues Andrew Tang, associate portfolio manager; Charles Shriver, cochair of the Asset Allocation Committee and portfolio manager; Stefan Hubrich, head of Global Multi-Asset Research; Rob Panariello, associate director of research; and I have taken a deep dive into the momentum factor.

Our results are counterintuitive. Andrew worked days, nights, and weekends to accommodate our countless requests to rerun the numbers and try different methodologies to kick the tires on our conclusions in time for our monthly Asset Allocation Committee meeting.

Here’s what we found:

Historically, high momentum was a positive signal for market returns. (However, that’s an average result with fat tails—more on this shortly.)

High momentum doesn’t always indicate excessive speculation. Often, momentum and quality (strength in fundamentals) are correlated, as they are currently. When momentum works, it’s not always because “fundamentals don’t matter.”

My conclusion is the following: Don’t fear the MOMO. I’m not telling you to load up on risk assets with a concentrated position in large-cap tech. But I would not hit the panic button. A fully invested and balanced approach, with disciplined rebalancing from growth toward value, leading to a tilt toward value, seems warranted. That’s how our Asset Allocation Committee is positioned.

Let’s review the research that led us to this conclusion—and why the results surprised us.

Momentum effectiveness

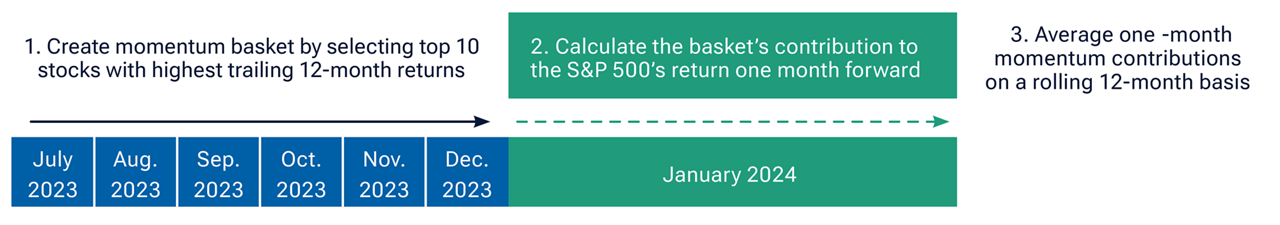

We built a new measure to evaluate what we term “momentum effectiveness.” Instead of using the traditional long-short academic factor construction approach, we used a simpler, more intuitive methodology.

We simulated what a naïve momentum investor might do. Looking back at monthly performance statistics, we created a basket of the top 10 S&P 500 Index constituents based on their trailing 12-month returns. We then held them before rebalancing again the following month.

To normalize for market returns, we calculated the momentum basket’s monthly contribution to the S&P 500’s total return.

Last, we calculated the rolling 12-month average of this measure.

To illustrate:

(Fig. 1) Is momentum working?

For illustrative purposes only.

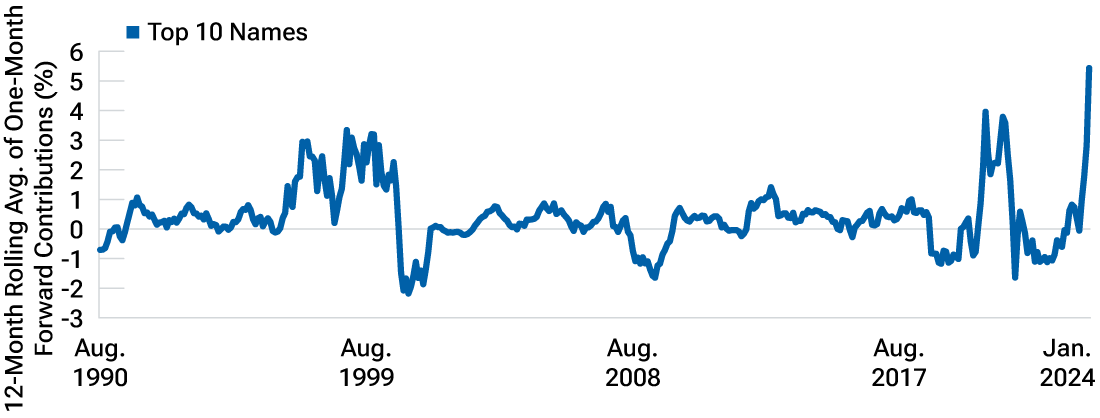

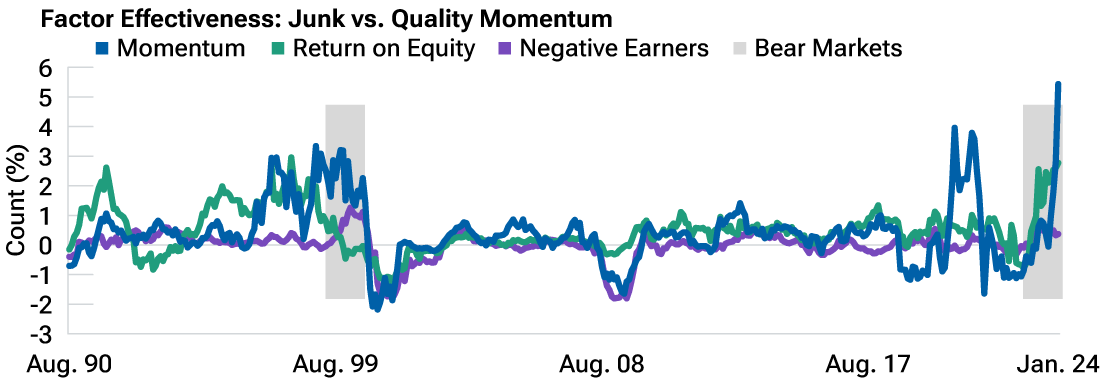

We replicated this methodology to calculate the effectiveness of the quality factor (ranked by return on equity) and the negative earners or “junk” factor (ranked by the most negative earnings). The chart below shows that momentum effectiveness is at an all-time high based on data stretching back to the early 1990s.

(Fig. 2) Momentum effectiveness

August 1990—February 2024.

Source: Standard & Poor’s, IDC. Analysis by T. Rowe Price.

Several factors drive momentum effectiveness. Excessive speculation (FOMO) is one of them. However, improving fundamentals also tend to boost momentum.

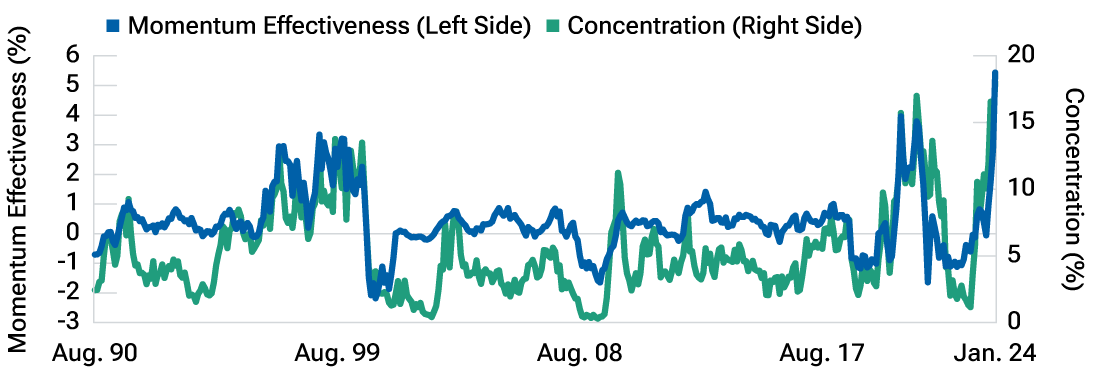

The chart below shows that momentum and market concentration tend to coexist. Here, we define concentration as the percentage of the market’s trailing 12-month returns explained by the top 10 contributors. Recently, a handful of large-cap tech stocks have driven almost all the gains in the S&P 500. Concentration, like momentum effectiveness, is at an all-time high. The momentum basket is now composed of large-cap stocks. Sell-side research firm Piper Sandler showed that the weight of high-momentum stocks in the index is at an all-time high going back to 1929.1

(Fig. 3) Momentum effectiveness and concentration

August 1990—February 2024.

Source: Standard & Poor’s, IDC. Analysis by T. Rowe Price.

If winners keep winning forever, a few companies will eat the world. Passive index investors pushing their marginal dollars into stocks in proportion to market capitalizations probably exacerbates this effect. However, that debate is outside the scope of this analysis.

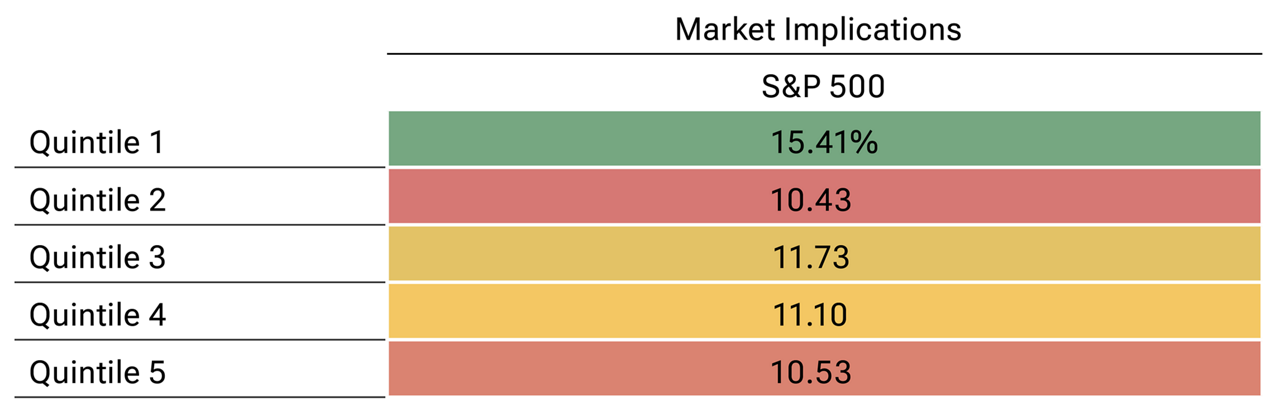

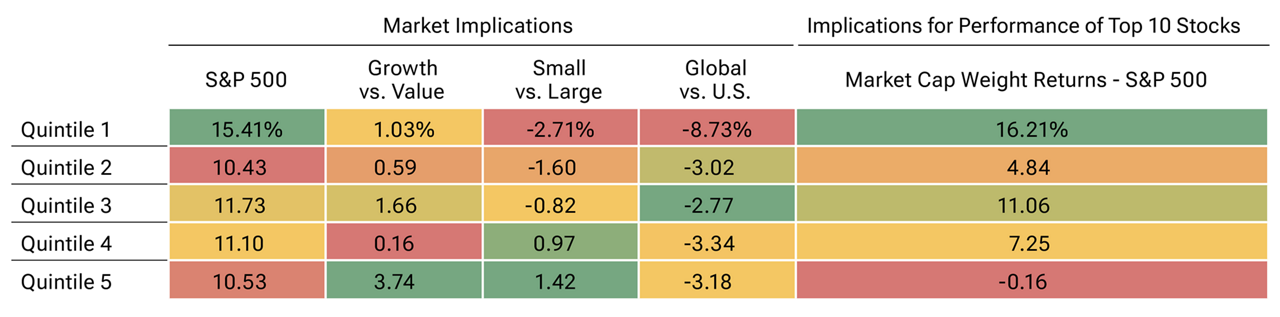

The immediate question is whether this is a bubble. Is a crash in large-cap tech right around the corner? Not necessarily. Look at the table below. The average 12-month forward return of the S&P 500 was 15.4% when momentum effectiveness was in its top quintile, as it is now.

(Fig. 4) Average 12-month forward performance of S&P 500 as a function of momentum effectiveness

August 1990—February 2024.

Source: Standard & Poor’s, IDC. Analysis by T. Rowe Price.

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

However, like the statistician who had his head in the freezer and his feet in the oven and claimed to feel great on average, this 15.4% number is misleading. It blends strong continued momentum during the mid-1990s and the COVID recovery (2020–2021) with the spectacular crash of momentum effectiveness when the internet bubble burst in 2000.

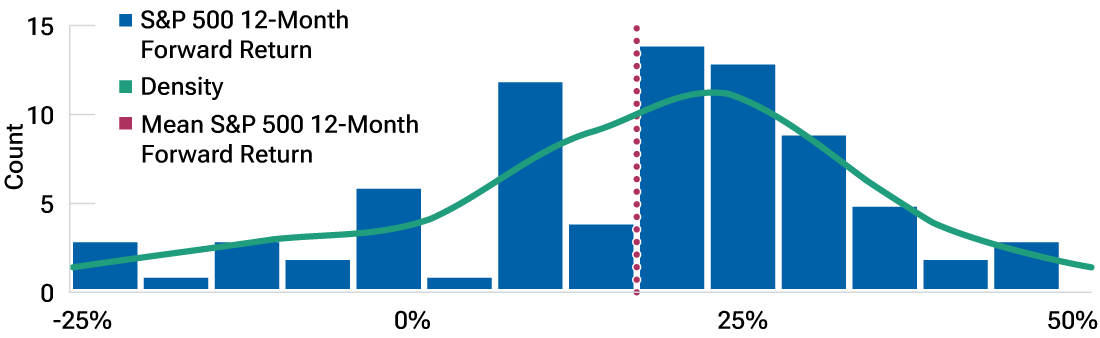

Below is the 12-month forward market returns distribution when momentum effectiveness was in its top quintile. The average is 15.4%, but notice the large left tail, which is mostly from the 2000 crash.

Before the crash of 2008, there was one blip on the radar: Momentum effectiveness was in its top quintile for one month in September 2007. In the years before the financial crisis, however, momentum effectiveness was weak. It was in its bottom quintile before the crash in the fall of 2008. It was also in its bottom quintile before the bear markets of 2018 and 2022.

So, when momentum effectiveness was high, there were plenty of times when the market did well in the following 12 months. Three bear markets (2008, 2018, 2022) occurred when momentum effectiveness was at its bottom quintile.

(Fig. 5) Distribution of S&P 500 Index forward 12-month returns in top quintile of momentum effectiveness

August 1990—February 2024.

Source: Standard & Poor’s, IDC. Analysis by T. Rowe Price.

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

My point is that the current situation does not necessarily indicate bubble risk. The chart below provides additional evidence to support this view.

In 1999 and early 2000, momentum effectiveness was correlated with what we might call negative-earners effectiveness more than quality effectiveness. It was a “junk rally.”

The situation is reversed now. Companies in the momentum basket have strong fundamentals. The correlation between momentum and quality effectiveness is reminiscent of 1996–1997, not 1999. Momentum effectiveness is more extreme now than ever before, but to a certain extent, so is the “momentum” in fundamentals. NVIDIA is making a lot of money. Its earnings were up 486% year over year in the fourth quarter.2 Since its earnings have grown faster than its share price, NVIDIA’s price‑to-earnings ratio is down, not up.

(Fig. 6) Momentum isn’t always the culprit in bear markets (Part II)

August 1990—February 2024.

Source: Standard & Poor’s, IDC, Compustat. Analysis by T. Rowe Price.

Still, we need to watch whether momentum and quality effectiveness start to diverge. That’s when my finger will get closer to the red button.

And no, a market broadening does not necessarily mean a junk rally. There are plenty of value and small-cap companies with high returns on equity (for a discussion on small- and mid‑cap quality, see linkedin.com/pulse/market-broadening-s%25C3%25A9bastien-page-xvsme/).

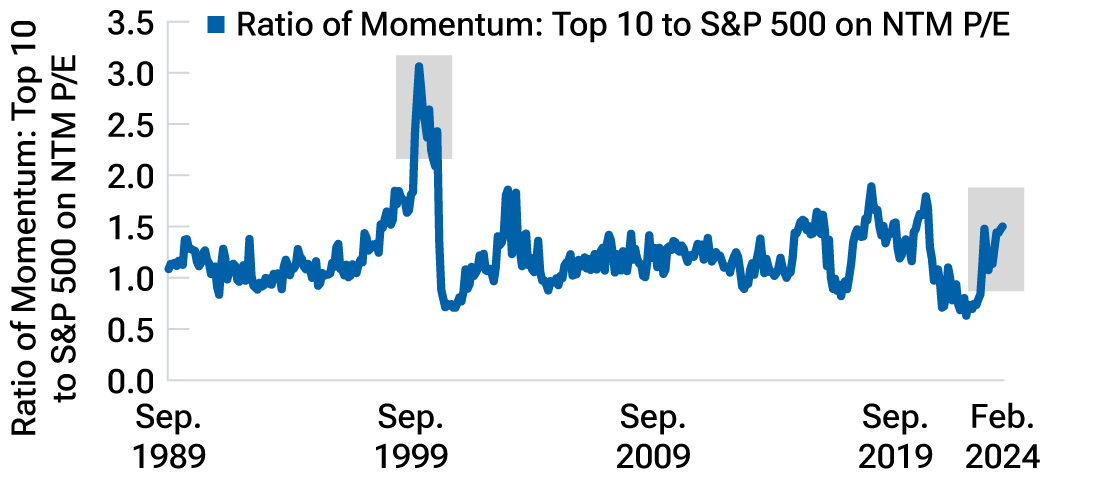

One last argument against the panic narrative: The relative valuation of the momentum basket is nowhere near its 1999–2000 level, as shown below.

(Fig. 7) Ratio of momentum: Top 10 to S&P 500 Next 12 Months Price/Earnings (NTM P/E)

September 1989—February 2024.

Source: Standard & Poor’s, IDC, Compustat. Analysis by T. Rowe Price.

The bottom line is that momentum and market concentration bear watching, but we remain fully invested and diversified between growth and value.

(Fig. 8) Average 12-month forward performance by momentum effectiveness quintile

August 1990—February 2024.

Source: Standard & Poor’s, IDC, GPAR. Analysis by T. Rowe Price.

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Addendum

Andrew was so fast and precise in running these analyses that we kept peppering him with follow-up questions. Below is a summary of this Q&A. The supporting table follows.

Q: What happened to the stocks in the momentum basket when momentum was extreme (looking 12 months forward)?

A: The conclusions are similar to what we found for market returns: Momentum stocks did well on average but with a fat left tail when it crashed following junk rallies.

Q: Does this analysis reveal anything about value versus growth?

A: We didn’t find anything conclusive in the data. Tech stocks sometimes drive momentum, but not always. Out of sample, momentum effectiveness was a relatively weak signal for value versus growth returns.

Q: What about small versus large?

A: As expected from our analysis of market concentration, large‑cap stocks tend to do better out of sample when momentum effectiveness is high.

Q: And global versus U.S.?

A: When momentum effectiveness is in its top quintile, U.S. stocks tend to outperform non-U.S. stocks.

Certain assumptions have been made for modeling purposes, and this material is not intended to predict future events. Please see Vendor Indices Disclaimers for more information about the sourcing information. For definitions of terms, please see: troweprice.com/en/us/glossary.

1I want to credit an excellent research report from Piper Sandler (Portfolio Strategy, Macro Research, March 13, 2024) for highlighting some of these ideas, albeit with a different methodology.

2NVIDIA earnings: fortune.com/2024/02/22/nvidia-earnings-growing-faster-than-stock/

Additional Disclosure

Copyright © 2024, S&P Global Market Intelligence (and its affiliates, as applicable). Reproduction of any information, data or material, including ratings (“Content”) in any form is prohibited except with the prior written permission of the relevant party. Such party, its affiliates and suppliers (“Content Providers”) do not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, completeness, timeliness or availability of any Content and are not responsible for any errors or omissions (negligent or otherwise), regardless of the cause, or for the results obtained from the use of such Content. In no event shall Content Providers be liable for any damages, costs, expenses, legal fees, or losses (including lost income or lost profit and opportunity costs) in connection with any use of the Content. A reference to a particular investment or security, a rating or any observation concerning an investment that is part of the Content is not a recommendation to buy, sell or hold such investment or security, does not address the suitability of an investment or security and should not be relied on as investment advice. Credit ratings are statements of opinions and are not statements of fact.

Important Information

This material is provided for informational purposes only and is not intended to be investment advice or a recommendation to take any particular investment action.

The views contained herein are those of the authors as of April 2024 and are subject to change without notice; these views may differ from those of other T. Rowe Price associates.

This information is not intended to reflect a current or past recommendation concerning investments, investment strategies, or account types, advice of any kind, or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any securities or investment services. The opinions and commentary provided do not take into account the investment objectives or financial situation of any particular investor or class of investor. Please consider your own circumstances before making an investment decision.

Information contained herein is based upon sources we consider to be reliable; we do not, however, guarantee its accuracy.

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. All investments are subject to market risk, including the possible loss of principal. Stock prices can fall because of weakness in the broad market, a particular industry, or specific holdings. Small-cap stocks have generally been more volatile in price than the large-cap stocks. The value approach to investing carries the risk that the market will not recognize a security’s intrinsic value for a long time or that a stock judged to be undervalued may actually be appropriately priced. Growth investments are subject to the volatility inherent in common stock investing, and their share price may fluctuate more than that of a fund investing in income-oriented stocks. All charts and tables are shown for illustrative purposes only. There is no guarantee that any forecasts made will come to pass.

T. Rowe Price Investment Services, Inc., distributor. T. Rowe Price Associates, Inc., investment adviser.

202404-3517316

Next Steps

Gain our latest thinking on the markets.

Contact a Financial Consultant at 1-800-401-1819.