Putting cash to work in 2024

January 2024, From the Field

Key Insights

- Pandemic-fueled fiscal and monetary stimulus pumped up the savings of U.S. households and businesses. Much of this cash found its way into money market funds.

- With short-term U.S. interest rates likely having peaked, we think cash exiting money market funds is likely to move into shorter-term bonds, at least initially.

- However, a consensus that the U.S. economy is headed for a soft landing also could draw investors into equities, particularly sectors that lagged amid rate concerns.

Written by

Christina Noonan, CFA

Portfolio Manager, Multi‑Asset Division

Christina Noonan, CFA

Portfolio Manager, Multi‑Asset Division

Som Priestley, CFA

Multi‑Asset Strategist and Portfolio Manager

Som Priestley, CFA

Multi‑Asset Strategist and Portfolio Manager

Douglas Spratley, CFA

Head of the Cash Management Team and Portfolio Manager

Douglas Spratley, CFA

Head of the Cash Management Team and Portfolio Manager

A wall of money is hanging over U.S. financial markets—in the form of a huge stockpile of liquidity parked in money market funds and other short-term liquid accounts. Where those funds move next, and when, could be a decisive factor in the future performance of both stocks and bonds.

Our bottom‑line conclusion is that cash seeking higher returns is likely to move into shorter‑term bonds, given attractive yield levels and a potential for price appreciation as yields move lower. However, if expectations of a soft landing for the U.S. economy becomes the market consensus in 2024, cash also could flow into equities, especially the rate‑sensitive sectors that suffered most during the Federal Reserve’s tightening campaign.

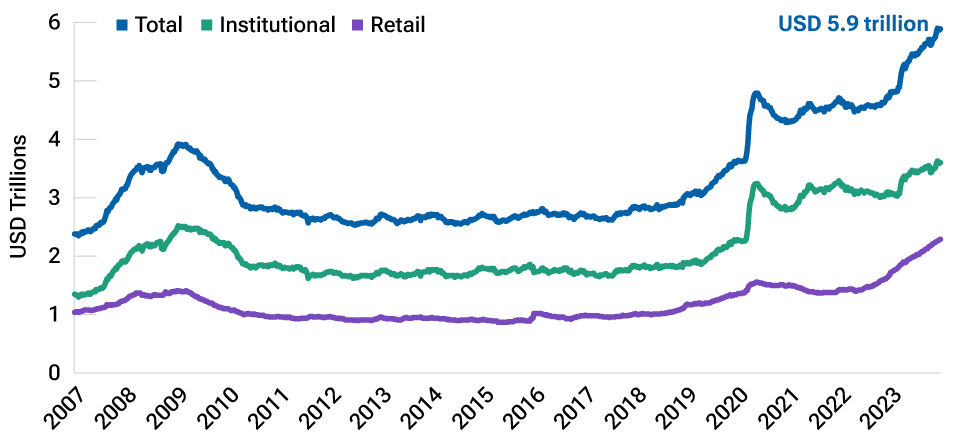

The potential amounts involved are unprecedented in dollar terms, although still below prior peaks as a percentage of U.S. equity market capitalization. As of mid‑December 2023, U.S. money market funds alone held almost USD 6 trillion in assets (Figure 1), up more than 60% since December 2019, on the eve of the pandemic.

U.S. investors are flush with liquidity

(Fig. 1) U.S. money market fund assets.

As of December 27, 2023.

Source: Investment Company Institute.

In large part, the surge in money market assets is a legacy of the pandemic. Nearzero interest rates and massive bond purchases by the U.S. Federal Reserve, coupled with heavy stimulus payments from the U.S. Treasury, pumped a flood of money into the financial system. Households and businesses saved much of that money and amid the uncertainty, stashed it in liquid products

Although the pandemic is in the rear‑view mirror, investors have had several other incentives to remain liquid for the past several years:

- Surging inflation and rising rates led to one of the worst bond bear markets in history, making longer‑term fixed income assets an unattractive place throughout much of 2022 and into 2023.

- Equities generally sold off along with fixed income assets during that period, reducing the benefits of diversification within traditional stock/bond portfolios.

- The Fed’s rapid rate hikes lifted yields on money market funds and short‑term accounts from near zero to above 5%, improving the rewards for staying liquid.

A look at past economic cycles suggests that this strong liquidity preference will ease at some point, especially if the U.S. economy avoids a deep recession and the Fed moves closer to cutting rates. Investor shifts could send a wave of cash into risk assets.

However, the timing of this move, and the specific asset classes on the receiving end of it, will depend on a number of variables that are hard to forecast, including the direction and pace of future Fed policy moves, lingering inflationary pressures, risks to economic growth, and—not least—investor behavior in the face of uncertainty.

Investor motives also could matter: Assets parked in money market funds to avoid the 2022–2023 stock and bond sell-offs could return to risk assets, while cash shifted from bank savings accounts appears more likely to remain in money market funds as long as they maintain a yield advantage over savings accounts. Mutual funds are not insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. While money market funds typically seek to maintain a share price of USD 1.00, there is no guarantee they will do so.

What recent history suggests about timing

A review of past Fed policy cycles suggests that investors typically fared best by deploying their liquid assets before or at the peaks of Fed tightening campaigns. This reflects the fact that as the Fed turned more accommodative, stocks and bonds both tended to perform well as rates were falling. With stocks and bonds both delivering positive returns, diversified portfolios also typically generated positive returns when rates were falling.1

Deploying cash ahead of rate peaks typically was beneficial

(Fig. 2) Subsequent average 12‑month excess returns versus a cash proxy.*

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. For illustrative purposes only. This is not representative of actual investments and does not reflect any fees and expenses associated with investing. Indexes cannot be invested in directly.

Sources: Bank of America, Bloomberg Finance L.P., Morningstar, S&P (see Additional Disclosures). All data analysis by T. Rowe Price.

*Cash proxy = 90‑Day U.S. Treasury Bill. Stocks = S&P 500 Index. Bonds = Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index. 60/40 portfolio was allocated 60% to the S&P 500 Index and 40% to the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index and reweighted monthly. This analysis covers the prior four Fed rate hike cycles. The current rate hike cycle is not included. Interest rate peaks = highest levels for the Fed’s federal funds rate target in February 1995, May 2000, June 2006, and December 2018.

To highlight these trends, T. Rowe Price analysts examined the performances of stocks, bonds, and a hypothetical 60/40 portfolio over four recent Fed policy cycles.2 Their analysis focused on the interest rate peaks reached in those cycles and reviewed the hypothetical impact on 12‑month returns of investing at various points before, at, and after each of those peaks (Figure 2).3

- The pattern for bonds was relatively clear. On average, liquid assets redeployed to bonds three months and six months before an interest rate peak outperformed a cash proxy over the subsequent 12 months. Bonds also outperformed cash over 12‑month periods starting three and six months after a peak, but excess returns were highest in the periods approaching a peak, as longer‑duration bonds significantly outperformed in those time frames.

- The performance track record for equities was not as clear‑cut. On average, stocks outperformed a cash proxy over 12‑month periods that started before an interest rate peak and offered the best relative forward (i.e., subsequent) returns at peak interest rates. However, stocks underperformed or showed only marginal outperformance for periods starting after a peak.

- The 60/40 portfolio outperformed a cash proxy over all the periods examined, except in 12‑month periods starting one year before an interest rate peak. The average margin of outperformance was greatest when investing at the peak or three and six months before a peak.

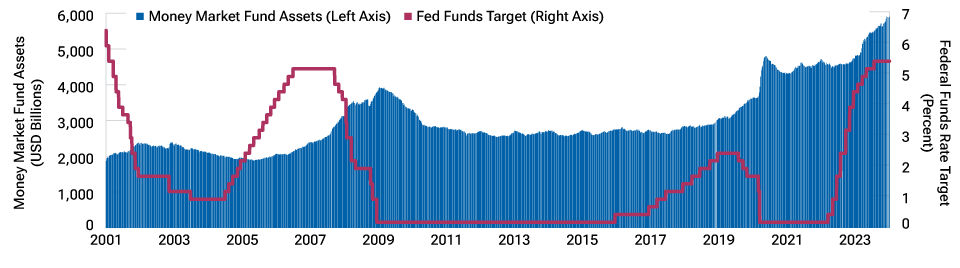

Cash flows lagged Fed rate cuts in past cycles

(Fig. 3) U.S. money market fund assets and the federal funds rate target.

As of December 27, 2023.

Sources: Investment Company Institute, Federal Reserve Board.

Flows may lag rates

Although the past four Fed policy cycles suggest that investors could have benefited most by shifting from cash to longer‑term fixed income assets and stocks either before or at an interest rate peak, actual investor behavior suggests they often have been slow to move, even after Fed rate cuts started pushing money market yields lower.

Figure 3 shows that in each of the past three Fed cycles, money market fund assets didn’t stop rising until well after the Fed had started cutting rates. In the past two cycles, these balances continued to grow even after short‑term rates had bottomed out.

In part, this reluctance to commit cash even when rates (and money market yields) were falling likely reflected the fact that Fed rate cuts often happen because the U.S. economy is weakening, and risk assets are lagging. In the last two cycles, for example, rapid Fed rate cuts were aimed at stabilizing both the economy and the markets in the early stages of the global financial crisis (2008) and the pandemic (2020). Frozen by extreme uncertainty, many investors chose to stay liquid even as the Fed ramped up policy easing.

Still, history suggests that investors slow to put liquid balances to work around the end of a Fed tightening campaign risked sacrificing considerable return potential.

Not all flows are alike

Because record flows into retail and institutional money market funds were driven by a variety of factors, where and when they are likely to go next are complicated questions.

Money market fund assets held in retail brokerage accounts seem more likely to move into equities, credit, and other risk assets. But many might be inclined to remain in those funds, as yields probably will still be attractive even at 3%–4% levels if inflation continues to slow and real (inflation‑adjusted) rates of return remain positive.

For institutional clients who fled banks to mitigate specific credit risks during the regional banking crisis in early 2023, money market funds were just one option. Many chose to invest directly in U.S. Treasury securities or limited their transfers to government money market funds. But with short‑term Treasury yields widely expected to move lower in 2024 as the Fed eases, money market funds could provide a yield advantage that attracts inflows from institutional investors focused on comparative returns among “cash equivalent” investments.

These varied sources of inflows across investor types suggest that at least part of today’s massive stockpile of liquidity is not destined to move into risk assets, no matter how attractive they may appear to be.

This cycle may be different

Whether investors will benefit from aggressively redeploying liquid assets as the Fed shifts to policy easing or would be better off taking a more cautious approach will depend on actual economic and market conditions. We see several potential challenges that could influence the movement into risky assets.

- U.S. inflation peaked higher than in other recent Fed policy cycles. Despite its recent downward trend, if inflation remained above target or inflected higher, it could keep short rates higher for longer, keeping investors entrenched in their money market funds.

- U.S. equities appear expensive on a historical basis, reflecting the influence of a relative handful of mega‑cap technology stocks. However, broader market valuations—notably among some rate‑sensitive equity sectors such as U.S. small-caps and emerging markets—are attractive. These sectors could be poised to benefit the most if money flows back to stocks.

- The U.S. yield curve is more inverted than at similar points in recent Fed cycles, leaving investors with less incentive to move out the yield curve, which features lower yields and higher rate volatility exposure than in past cycles.

- A technical factor also could discourage investors from moving into longer‑term bonds. Rising federal budget deficits mean the U.S. Treasury will need to bring a larger supply of debt to market. This means longer‑term bond yields could be biased higher relative to other recent Fed cycles.

Wall of money scenarios

Soft landing

- Moderate growth & continued disinflation

- Fear of missing out

- Stocks & bonds outperform

Deep recession

- Sharper decline in economic growth

- Cash remains attractive

- Bonds outperform; stocks under pressure

Stagflation

- Inflation reaccelerates while growth stalls

- Investors increase cash holdings

- Stocks & bonds could underperform

Three potential scenarios for 2024

Given the many uncertainties, we think it makes sense to think about the wall of money in terms of possible scenarios rather than a single outcome. As of the end of December, three potential scenarios struck us as most plausible in 2024.

A soft landing for the U.S. economy, with slower but steady growth, a still healthy labor market, and continued disinflation.

This is our base‑case scenario. While soft landings historically have been difficult to pull off, it is looking increasingly likely that the Fed will be able to bring down inflation without triggering a more severe downturn in growth and employment. This backdrop would set up an attractive environment for risk assets and longer‑duration bonds.

In this scenario, investors might fear missing out on broad rallies in both stocks and bonds—like the risk‑on rally experienced in the fall of 2023. This could send sizable waves of liquidity pouring into both markets. We could see investment performance broadening to areas like U.S. small‑cap equities and more rate‑sensitive markets outside the U.S., particularly the emerging markets. Investors who remain in money market funds would face a slow relative deterioration in returns as the Fed moves to cut rates.

A more dramatic decline in U.S. economic growth, forcing the Fed to act faster to cut rates.

While the Fed sees growth and inflation risks as more balanced now, the aggressive tightening seen in 2022 and early 2023 may still have lagged impacts serious enough to send the U.S. economy into recession.

Should the risks tilt toward such a hard landing, forcing the Fed to cut rates quickly to counteract a U.S. economic stall, risk assets will be at a disadvantage while longer‑duration bonds should benefit. In this scenario, investors waiting on the sidelines in money market funds would avoid market volatility but likely would underperform bonds further out the curve as the Fed lowered rates.

Economic malaise as growth churns down and inflation reaccelerates.

While inflation is trending toward the Fed’s presumed 2% target, an unexpected resurgence in prices amid declining growth could invoke fears of stagflation. Renewed conflicts in the Middle East and their impacts on shipping lanes and supply chains have reminded investors that economic shocks can quickly drive inflation higher.

This scenario could resemble the synchronized sell-off in stocks and bonds seen in 2022. The need for a hawkish pivot by the Fed would reignite market volatility, particularly if accompanied by a deteriorating labor market. If the Fed prioritizes price stability over growth, risk assets and long‑term bonds both could be pressured. In such an environment, money market funds would remain attractive and possibly could lure even more inflows.

Money market funds may keep their luster

If the soft landing scenario, with growth moderating and continued disinflation—while avoiding a severe downturn—continues to play out, it would be favorable for bonds as the yield curve normalizes. However, given the steeply inverted yield curve and the potential for increased Treasury supply to impact longer‑duration Treasuries, short‑ to intermediate‑term bonds could be poised to outperform.

Credit markets still offer attractive yields but may have limited upside given tight spreads4 across most sectors, although declining Treasury yields should be a positive for bond prices and provide a cushion against potential spread widening.

While U.S. equity valuations on average are historically high, and the momentum seen in the second half of 2023 may have been overdone, pockets of opportunity could benefit from broader participation by the sectors that were impacted most by rising interest rates and a strong U.S. dollar.

For investors who moved into money market funds principally due to risk aversion and who feel left behind by the late 2023 rally in risk assets, we believe 2024 should continue to provide pockets of opportunity.

Attractive yields but narrow spreads: The credit dilemma

1 Diversification cannot assure a profit or protect against loss in a declining market.

2 Terry Davis and Andrew Wick, “Is Now the Time to Redeploy to Cash?” T. Rowe Price Insights on Portfolio Construction Solutions, November 2023.

3 See Figure 2 for the representative benchmarks for cash, bonds, stocks, and a 60/40 portfolio.

4 Credit spreads measure the additional yield that investors demand for holding a bond with credit risk over a similar‑maturity, high‑quality government security.

Additional Disclosures

©2024 Morningstar, Inc. All rights reserved. The information contained herein: (1) is proprietary to Morningstar and/or its content providers; (2) may not be copied or distributed; and (3) is not warranted to be accurate, complete, or timely. Neither Morningstar nor its content providers are responsible for any damages or losses arising from any use of this information. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

The S&P 500 Index is a product of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, a division of S&P Global, or its affiliates (“SPDJI”), and has been licensed for use by T. Rowe Price. Standard & Poor’s® and S&P® are registered trademarks of Standard & Poor’s Financial Services LLC, a division of S&P Global (“S&P”); Dow Jones® is a registered trademark of Dow Jones Trademark Holdings LLC (“Dow Jones”); these trademarks have been licensed for use by SPDJI and sublicensed for certain purposes by T. Rowe Price. T. Rowe Price products are not sponsored, endorsed, sold or promoted by SPDJI, Dow Jones, S&P, or their respective affiliates, and none of such parties make any representation regarding the advisability of investing in such product(s) nor do they have any liability for any errors, omissions, or interruptions of the S&P 500 Index.

CFA® and Chartered Financial Analyst® are registered trademarks owned by CFA Institute.

Important Information

This material is provided for informational purposes only and is not intended to be investment advice or a recommendation to take any particular investment action.

The views contained herein are those of the authors as of January 2024 and are subject to change without notice; these views may differ from those of other T. Rowe Price associates.

This information is not intended to reflect a current or past recommendation concerning investments, investment strategies, or account types, advice of any kind, or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any securities or investment services. The opinions and commentary provided do not take into account the investment objectives or financial situation of any particular investor or class of investor. Please consider your own circumstances before making an investment decision.

Information contained herein is based upon sources we consider to be reliable; we do not, however, guarantee its accuracy.

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. All investments are subject to market risk, including the possible loss of principal. Money market mutual funds generally offer the greatest level of flexibility and liquidity along with the lowest risk of principal loss among the available short-term investment products. Fixed-income securities are subject to credit risk, liquidity risk, call risk, and interest-rate risk. As interest rates rise, bond prices generally fall. Small-cap stocks have generally been more volatile in price than large-cap stocks. All charts and tables are shown for illustrative purposes only.

T. Rowe Price Investment Services, Inc.

© 2024 T. Rowe Price. All Rights Reserved. T. Rowe Price, INVEST WITH CONFIDENCE, and the Bighorn Sheep design are, collectively and/or apart, trademarks of T. Rowe Price Group, Inc.

ID0006624 (01/2024)

202401‑3347680